Sam Houston Part IV – The Road To Texas

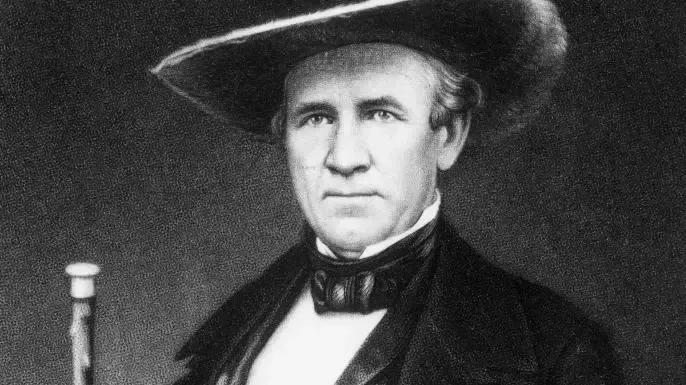

In our last installment, Sam Houston Part III – Early Political Career, we discussed the different roles Houston played in the early political scene in Tennessee, and how, with the help of several influential mentors and allies, he secured a seat in the U.S. House of Representatives in 1823, won reelection in 1825, and was elected as the state’s sixth governor in 1827. Houston’s place in Tennessee’s political arena seemed solidified, and he seemed well positioned for a future presidential run.

But, when Houston’s marriage to Eliza Allen, the daughter of wealthy Gallatin, Tennessee plantation owner John Allen collapsed soon after the couple’s wedding in January of 1829, he resigned the governorship amid controversy and a ruined reputation. After his resignation he returned to the Cherokee, who by this time had been relocated to Arkansas.

Because of Houston’s experience in government and his connections with then President Jackson, several local Native American tribes asked him to mediate disputes and communicate their needs to the Jackson Administration.

In late 1829, Houston was given a tribal membership and was sent by the Cherokee to Washington to negotiate several issues. Houston knew at this point that the Cherokee that remained east of the Mississippi would eventually be removed and attempted to broker a deal to provide supply rations for their journey.

In early 1832 Ohio Congressman William Stanbery alleged that Houston, in collusion with the Jackson administration, had submitted a fraudulent bid to provide the provisions to the Cherokee. Houston made numerous attempts to address the allegations with his accuser, but Stanbery ignored his letters. The two met on Pennsylvania Avenue on April 13, 1832, and Houston confronted Stanbery about not only the allegations but his failure to respond to his communiques. An argument ensued, which escalated to Houston giving Stanbery a sound beating with a walking cane. After the incident, the House of Representatives tried and convicted Houston, and Speaker of the House Andrew Stevenson formally reprimanded him, casting further shame on the statesman. A federal court also required Houston to pay damages of $500.

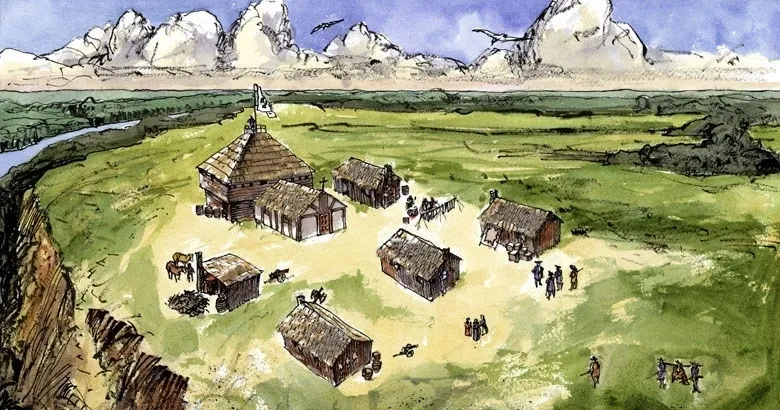

In mid-1832, Houston received letters from his friends William H. Wharton and John Austin Wharton trying to convince him to travel to Texas, which at the time was still a part of Mexico. There was growing unrest among the American settlers who had relocated there at the invitation of the Mexican government in an effort to increase the population of the area. Many of the Americans were dissatisfied with Mexican rule, and Houston, being dissatisfied with life in what was becoming a much more populated area in the states east of the Mississippi, accepted their invitation to come to Texas.

Houston arrived in Texas in December of 1832, and soon after, was granted land in Texas. He was then elected to represent Nacogdoches, Texas at the Convention of 1833, which was called for the purpose of petitioning Mexico for statehood. Houston was a strong proponent of statehood, and he chaired a committee that drew up a proposed state constitution. After the convention, Texan leader Stephen F. Austin petitioned the Mexican government for statehood, but was unable to come to an agreement with Mexican President Valentin Gomez Farias. In 1834, Antonio Lopez de Santa Anna became president, and although Austin had supported Santa Anna, the president, fueled by concerns that Austin was inciting support for independence among the settlers, had Austin arrested and imprisoned for nearly a year.

Thank you for allowing me to bring you these glimpses into our past. Please join us for our next installment; Sam Houston Part V – The Alamo & Beyond.

See the previous post Sam Houston Part III – Early Political Career here:

Sam Houston Part III – Early Political Career (familytreenuts.org)

Blaine K. Price, Historian

Family Tree Nuts