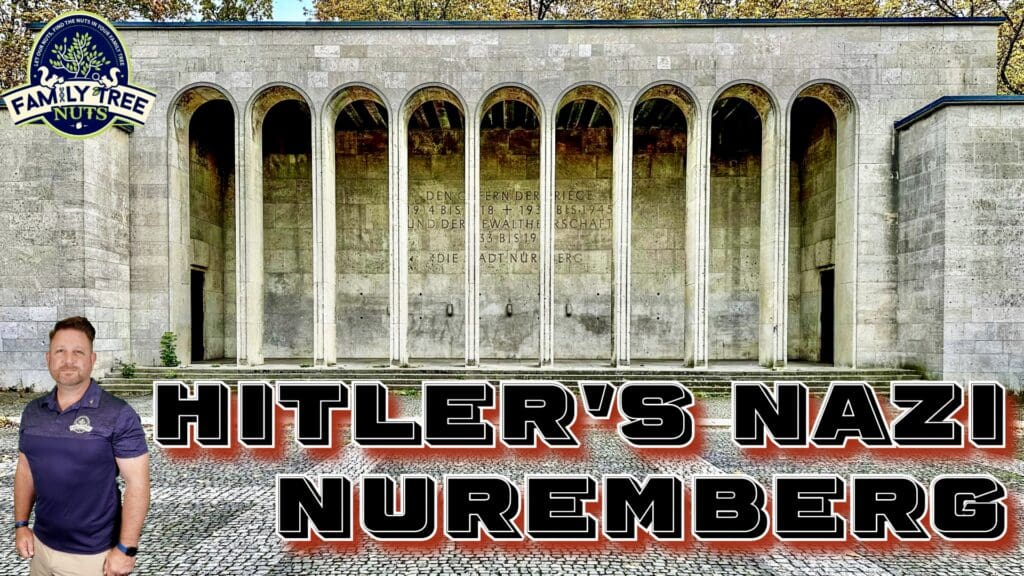

HITLER’S NAZI NUREMBERG

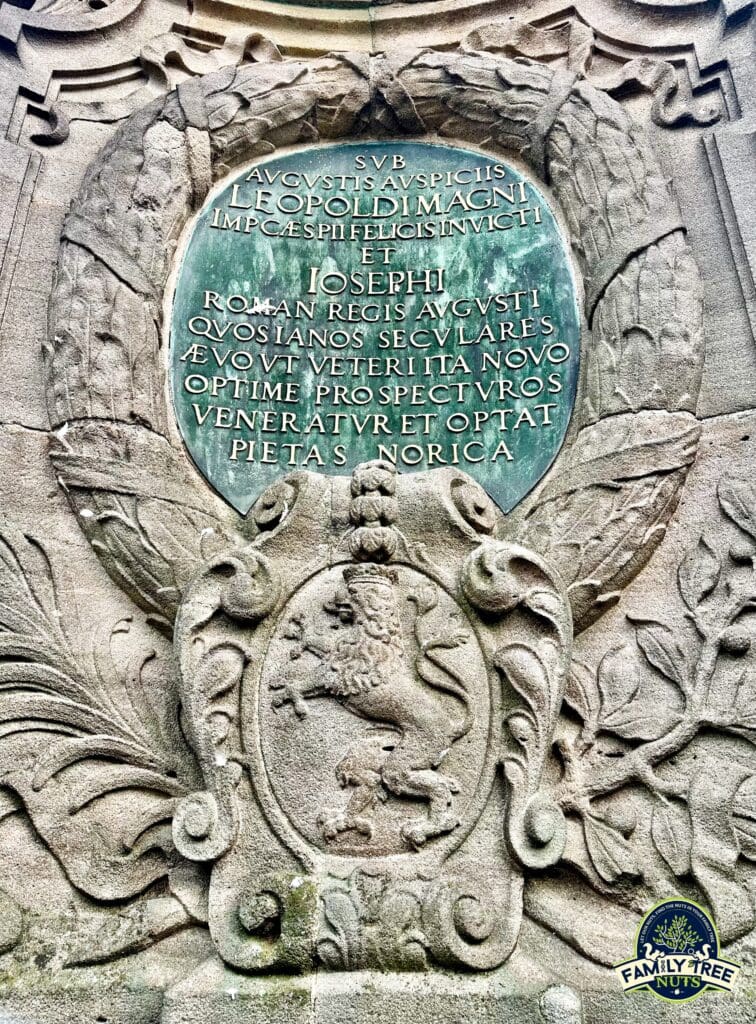

Welcome to Nuremberg, Germany—a city that played a central role in the Nazi Party’s rise and reign from 1933 to 1945. Located in Bavaria, Nuremberg’s historical significance stretches back to the Middle Ages, when it was a key center of the Holy Roman Empire and hosted imperial diets, or assemblies. This deep-rooted past made it an appealing choice for Adolf Hitler and the Nazi leadership when they selected it as the site for their annual party rallies starting in 1933. This city was a place that Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party claimed as their own, a city they molded into the beating heart of their ideology, their propaganda, and their dreams of eternal dominion.

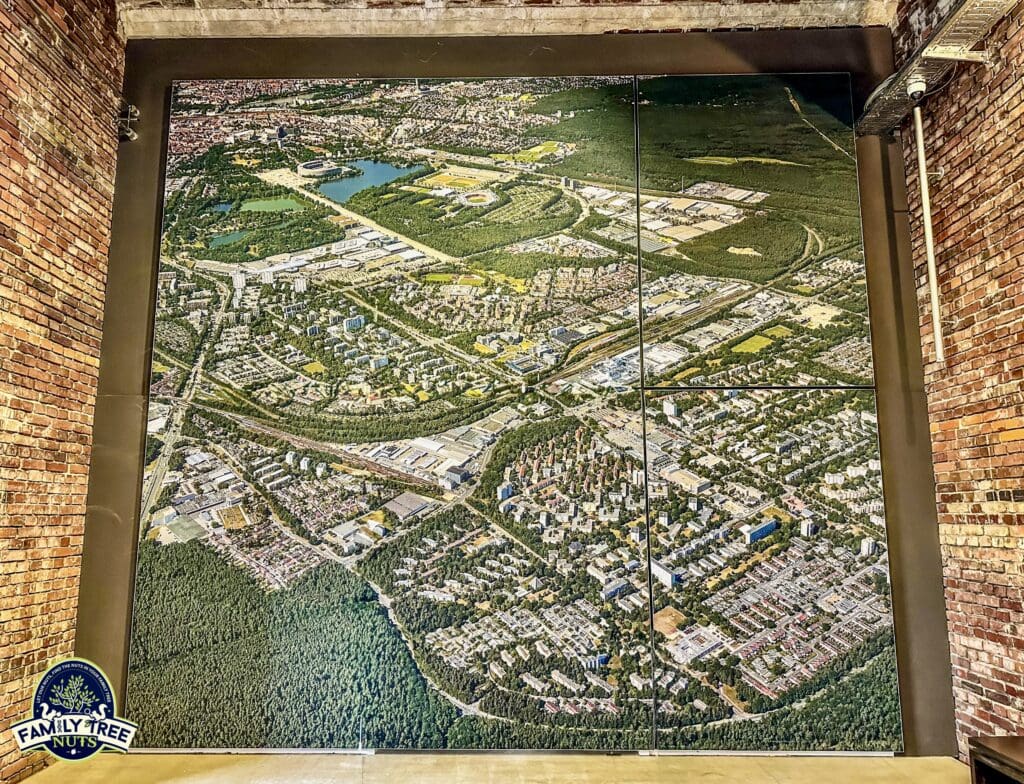

The Nazis chose Nuremberg deliberately. Its medieval heritage and central location in Germany provided a symbolic connection to the nation’s past, which Hitler exploited to legitimize his vision of a “Thousand-Year Reich.” Between 1933 and 1938, the city hosted six major Nazi Party rallies, each drawing hundreds of thousands of attendees—party members, military units, and civilians alike. These events, held on a sprawling 11-square-kilometer site known as the Nazi Party Rally Grounds, were meticulously planned to showcase Nazi power and unity.

Beyond the rallies, Nuremberg became a construction zone for ambitious projects under Hitler’s architect, Albert Speer. In this video, we will take you to the places that the regime invested heavily in transforming the city with structures. We will visit the history of the Ehrenhalle, Zeppelinfeld, the Congress Hall and it’s museum, and the Große Straße. Each location was designed to reflect Nazi ideals of grandeur and permanence. After World War II, Nuremberg’s role shifted again, hosting the International Military Tribunal from 1945 to 1946, where key Nazi leaders faced trial for war crimes. Today, these sites remain as historical landmarks, offering a window into the Nazi era.

Before we begin, a quick disclaimer: This is a recounting of history. We are not here to glorify Adolf Hitler or the Nazi regime, but to understand these places tied to their story. For obvious reasons, it’s important to not forget the history that happened here. In about thirty seconds, we will begin our tour.

Hey everybody this is Colonel Carson with Family Tree Nuts, and I’m a professional genealogist and a historian. We recently visited these locations in Munich, and I want to share these stories show you the sights, with all of you. At Family Tree Nuts, we build family trees for clients that either don’t know how, don’t have the time, or don’t want to pay those expensive membership fees. We’d love to honor your ancestors for you. We also make history videos all over the United States, and a few countries. If you like videos like these, be sure to subscribe to our YouTube channel. This video is one of many that we have from Germany, and about Hitler and the Nazi’s. Now back to the story.

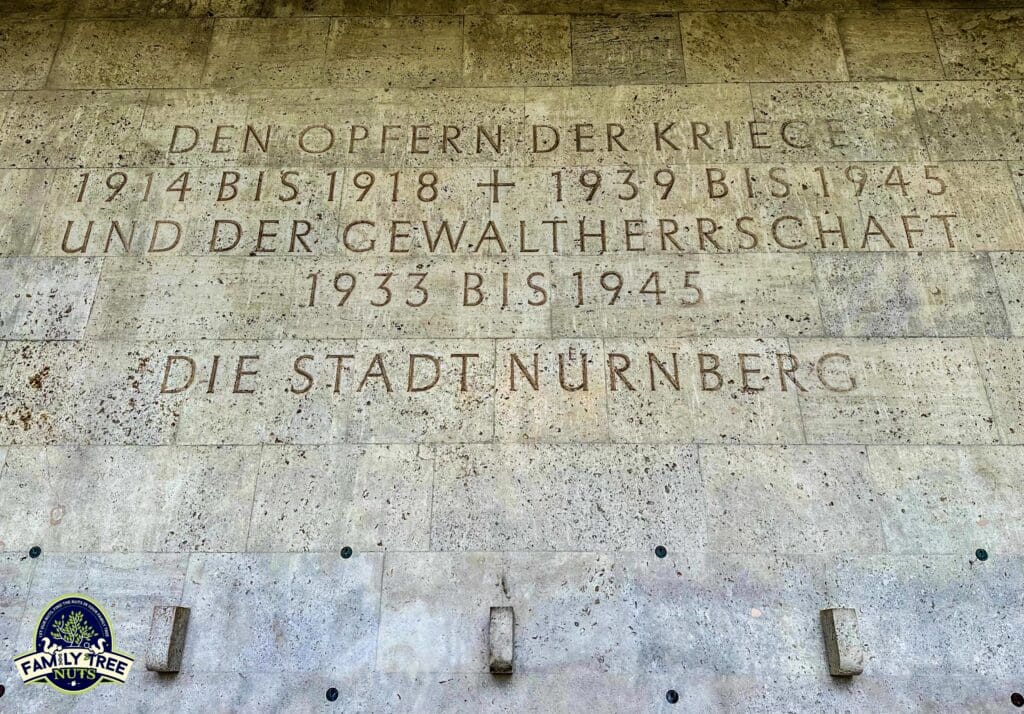

First, we arrive at the Ehrenhalle, or Hall of Honor, located in the Luitpoldhain Park within the Rally Grounds. This structure predates the Nazi era, built between 1927 and 1929 by architect Fritz Mayer to commemorate Nuremberg’s 2,600 soldiers killed in World War I. The Ehrenhalle features a neoclassical design—two rows of stone arches forming a U-shaped courtyard, with a low roof and an open interior. It stands approximately 20 meters long and 10 meters high, constructed from local sandstone.

When the Nazis took power in 1933, they repurposed the Ehrenhalle for their own ceremonies. The site’s original purpose as a war memorial aligned with their propaganda, emphasizing themes of sacrifice and national honor. During the annual party rallies, the Ehrenhalle became a focal point for rituals, particularly the commemoration of the 1923 Beer Hall Putsch—an attempted coup in Munich that marked an early milestone for the Nazi Party. On November 9th each year, Hitler and top officials, including Heinrich Himmler and Rudolf Hess, gathered here. In 1935, the Nazis added an eternal flame to the courtyard, reinforcing the site’s symbolic weight.

A notable feature for visitors today is the ability to stand and walk in the exact spots where Nazi leaders once stood. You can position yourself beneath the arches where Hitler paused during ceremonies or trace the path of SA and SS units as they marched through the courtyard. The site saw heavy use during rallies, with up to 60,000 participants filling the surrounding area for events like the 1937 rally, documented in photographs and films.

After the war, the Ehrenhalle returned to a quieter state. The eternal flame was extinguished, and the site was preserved as part of Nuremberg’s historical record. It remains intact, offering a tangible link to the Nazi era’s public displays.

Next, we move to Zeppelinfeld, a massive open field within the Rally Grounds, covering roughly 312 meters by 285 meters—about 84,000 square meters total. This isn’t a subtle place. It’s overwhelming, colossal, a theater of power carved from the earth. Its name originates from an event predating the Nazis: on 25 August 1909, the LZ 6, a Zeppelin airship, landed here during a demonstration flight, marking the site’s association with early aviation history. The Nazis later capitalized on this name, incorporating it into their Rally Grounds development.

Construction of the current Zeppelinfeld began in 1935 under Albert Speer’s direction. The field was designed to accommodate up to 200,000 people, surrounded by tiered grandstands built from limestone. At its northern end stands the Zeppelin Tribune, a 90-meter-wide platform with a central podium flanked by two wings. The tribune’s design drew inspiration from the Pergamon Altar in ancient Greece, reflecting the Nazis’ fascination with classical architecture. During rallies, Hitler delivered speeches from this podium, addressing crowds that swelled to 250,000 at peak events, such as the 1938 Reichsparteitag Großdeutschland, celebrating Germany’s annexation of Austria.

A striking detail is that you can stand today in the exact spot where Hitler gave those speeches. The podium remains accessible, offering a direct connection to the site’s history. The tribune also featured a gilded swastika atop its roof until 25 April 1945, when U.S. Army engineers dynamited it as a symbolic act of de-Nazification, captured on film by military crews.

Zeppelinfeld’s use didn’t end with the war. From 1945 to 1995, the U.S. Army occupied the Rally Grounds as part of their postwar presence in Nuremberg. They repurposed Zeppelinfeld for athletic events—baseball games, track meets—and as a parade ground for military drills. The 3rd Infantry Division, stationed nearby, maintained the site until their withdrawal in 1995, when it was returned to German control.

The field hosted its largest Nazi event in September 1937, with 1,300 searchlights creating Speer’s famous “cathedral of light,” a spectacle recorded in Leni Riefenstahl’s propaganda film Triumph of the Will. Today, the grandstands are deteriorating, but the site remains open to the public, a preserved piece of history spanning airships, rallies, and military occupation.

Next, we approach the Congress Hall—or, as it’s often called, the Coliseum. If Zeppelinfeld was a stage, this was meant to be the crown jewel—a gargantuan arena to house the Nazi faithful. Construction began in 1935, again under Albert Speer’s oversight, with a design inspired by Rome’s Colosseum. Unlike its Roman counterpart, which seats 50,000, this version was planned to hold 50,000 indoors under a massive roof, with an outer diameter of 290 meters and a height reaching 39 meters—though it was never completed. By 1943, World War II halted work, leaving the building as a horseshoe-shaped shell with an unfinished interior.

The Congress Hall was intended as the centerpiece of the Rally Grounds, a permanent venue for Nazi Party congresses. Its foundations required 1.2 million cubic meters of concrete, and its outer walls used red brick sourced from Franconia. The Nazis completed about two-thirds of the structure, including the exterior and some internal galleries, before resources were diverted to the war effort. Original plans included a glass roof and an elaborate entrance hall, but these remained on paper.

Today, the Congress Hall stands as a testament to Nazi architectural ambition. Visitors can explore its vast, empty interior, which echoes with the scale of what might have been.

Inside the Congress Hall’s northern wing lies the Documentation Center, opened on November 4, 2001, as a museum titled “Fascination and Terror.” The center occupies 1,300 square meters, with a modern glass-and-steel extension cutting through the Nazi-era brickwork. Its exhibits chronicle the rise and fall of the Nazi regime, using photographs, documents, and multimedia displays.

One notable artifact is the Reich banner—the black, red, and gold flag adopted by the Nazi Party in 1935 after the Nuremberg Laws were passed here. This flag, distinct from the earlier Weimar Republic tricolor, incorporated the swastika and symbolized the regime’s consolidation of power. The museum displays replicas and explains its adoption during the 1935 rally, when Hitler announced the laws stripping Jews of citizenship—a turning point in Nazi racial policy.

Other exhibits include rally footage, architectural models of the Rally Grounds, and timelines of Nuremberg’s role from 1933 to the postwar trials. Annual visitor numbers average 200,000, reflecting its status as a key educational site. The museum provides a factual lens on the Nazi era, detailing events like the 1938 rally, attended by 1.6 million people across the Rally Grounds, and the city’s destruction in 1945, when Allied bombings reduced 90% of Nuremberg to rubble.

Finally, we reach the Große Straße, or Great Street, a 2-kilometer-long, 40-meter-wide boulevard paved with 60,000 granite slabs. Construction began in 1935 and finished in 1939, designed by Albert Speer to serve as a parade route connecting the Rally Grounds to Nuremberg’s old town. Speer aligned the street with the Imperial Castle in the Old Town, a deliberate choice to create a symbolic link between Nuremberg as the city of the imperial diets—where Holy Roman emperors once met—and Nuremberg as the “City of the Party Rallies.”

The street was built to withstand heavy traffic, including tanks and marching columns. During the 1938 rally, it hosted a parade of 100,000 troops and 500 vehicles, documented in Nazi newsreels. Its granite surface, sourced from quarries in Lower Bavaria, was laid with precision to ensure durability. Plans called for it to extend further, but the war interrupted additional phases.

After 1945, the Große Straße saw limited use. The U.S. Army briefly utilized it for logistics, but it largely fell into disrepair. Today, it remains intact, though overgrown in places, serving as a historical pathway open to visitors.

Our tour ends here, having covered the Ehrenhalle, Zeppelinfeld, Congress Hall, its museum, and the Große Straße. These sites collectively represent the Nazi Party’s investment in Nuremberg—over 100 million Reichsmarks spent on the Rally Grounds alone—and their use of the city as a propaganda hub from 1933 to 1939. After the war, Nuremberg’s hosting of the trials, which convicted 19 Nazi leaders between 1945 and 1946, cemented its place in history.

Today, these landmarks are maintained by the city and the Bavarian state, drawing over 300,000 visitors annually to the Rally Grounds. They stand as factual records of an era, preserved for study and reflection. The Germans don’t hide from their history, they put it in full view to forever be used as a lesson for mankind.

So now we know the stories and have seen the sights in Nuremburg related to the Third Reich. What do you think? Have you ever been here before, or is it one you bucket list? What do you think of the history of the places? Do you think they should be bulldozed, or should the history be remembered? We’d love to hear what you have to say in the comments below. We are proud to share this information with all of you, and make sure you see our video from here at the link below. And remember, Family Tree Nuts, let out nuts find the nuts in your family tree.

-Colonel Russ Carson, Jr., Founder, Family Tree Nuts