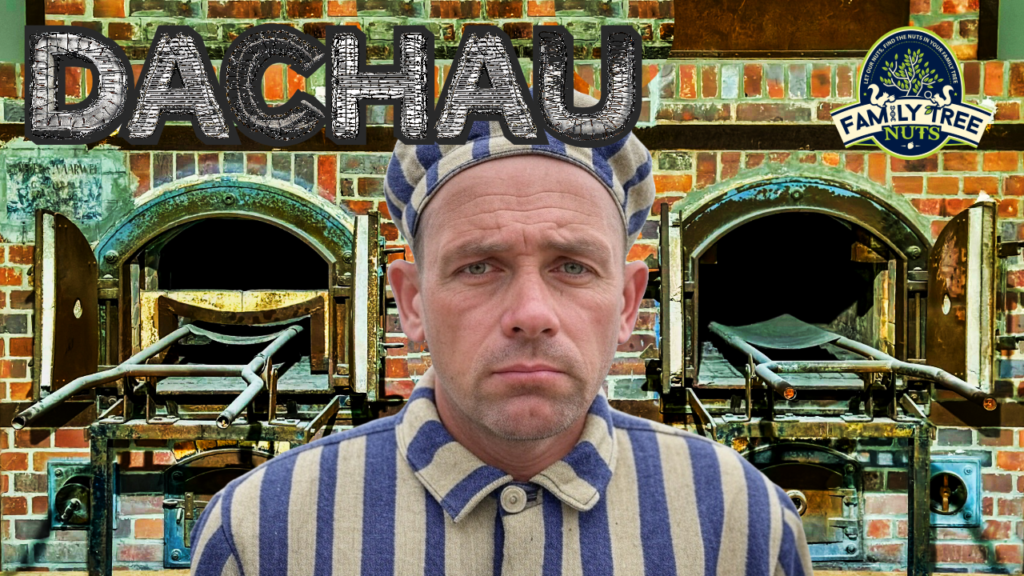

DACHAU, THE FIRST NAZI CONCENTRATION CAMP

Welcome to Dachau, the site of the first Nazi concentration camp, established in 1933. Located just north of Munich, Germany, Dachau operated for twelve years under the Nazi regime and is said to have imprisoned over 200,000 people from across Europe. Initially it was intended to hold political prisoners, Communists, Socialists, and other dissenters, but it later also held Jews, Romani, homosexuals, Jehovah’s Witnesses, and others. It was not an extermination camp, but a place of forced labor, punishment, and unimaginable suffering, where it is said that more than 41,500 lost their lives. Today, we’ll explore its history, tour its layout, and its legacy as a memorial to those who endured it.

Hey everybody this is Colonel Carson with Family Tree Nuts, and I’m a professional genealogist and a historian. We recently visited Dachau, and I want to share its story with all of you. Unlike most history that we document, this isn’t a fun one, but it’s an important to cover anyhow. In case you are wondering what Family Tree Nuts is, we build family trees for clients that either don’t know how, don’t have the time, or don’t want to pay those expensive membership fees. We’d love to honor your ancestors for you. We also make history videos all over the United States, and a few countries. If you like videos like these, be sure to subscribe to our YouTube channel. This video is one of several that we have from Germany and about Hitler and the Nazi’s. Now back to the story.

Our journey begins at the main gate, marked by the wrought-iron phrase “Arbeit Macht Frei”, which means, “Work Sets You Free.” This gate was the entrance for prisoners arriving between 1933 and 1945. Built in the early days of the camp, it was part of the initial infrastructure when Dachau opened on 22 March 1933, under Heinrich Himmler’s orders. For many that crossed these gates, they were never free again. Beyond this gate lay a tightly controlled world of barbed wire and watchtowers, where prisoners faced a harsh new reality.

Next, we move to the barracks area. Today, the outlines of the original 34 barracks are marked by concrete foundations, each numbered for clarity. These long, low buildings stretch out in rows—wooden skeletons of a brutal past. In 1933, Dachau was designed to hold 6,000 prisoners, but by 1945, it was overcrowded with over 30,000. Only two barracks have been reconstructed for visitors; the rest are left as outlines to show the scale.

Prisoner life began with arrival, where they were stripped of possessions, shaved, and given striped uniforms. Daily routines were relentless: roll call at dawn, often lasting hours, followed by 12-hour work shifts in nearby factories or quarries. Food was scarce—thin soup and bread rations kept prisoners weak. Beds were wooden bunks, stacked three high, with thin straw mattresses shared by multiple men. Toilets were rudimentary, a single block for hundreds, leading to disease and filth. Showers existed but were infrequent, often cold, and doubled as a means of humiliation rather than hygiene.

For pastimes, there was little. Some prisoners secretly played cards or chess with makeshift pieces, risking punishment if caught. Others found solace in whispered conversations—small acts of resistance against their captors.

We now enter the crematorium area, where fumigation cubicles stand. These small chambers were used to delouse clothing with chemicals, a response to rampant disease like typhus. Nearby is the waiting room, a stark holding space where prisoners stood before processing or punishment, uncertainty heavy in the air.

Adjacent are the showers—concrete and grim. These were not gas chambers; they served for cleaning, but some prisoner accounts do exist that the showers had been used for at least one gassing. Today, a bird’s nest rests in the wall—a quiet sign that life can emerge even from a place shadowed by death. This reminds us of nature’s resilience amid human-made horror.

Further in, we reach the crematorium ovens, which is the hardest place for most visitors. Two sets exist here. In the beginning of the camp era, those that died were taken to local crematoriums in the area, but as the death tolls rose from starvation and disease, the camp constructed its own. The first, a smaller twin oven, was built in 1940 but by 1942, with bodies piling up, a larger barracks-like structure was constructed, housing four ovens. These operated day and night, reducing thousands of corpses to ash—not as a method of execution, but disposal. It is stated that over 41,500 died here: 15,000 from malnutrition, 20,000 from diseases such as typhus, and roughly 6,500 from executions, medical experiments or exhaustion. The ovens stand as a stark testament to the scale of loss, their brick and steel preserved for history’s witness.

Outside, we find the memorial garden and ash grave. The garden is a quiet space of reflection, planted with trees and bordered by stones. Nearby, the ash grave holds the remains of thousands whose bodies were cremated, a collective resting place marked by a simple plaque. Adjacent is the Christian memorial grave, a cross-topped mound honoring the faith of many prisoners—Catholic priests and others—who perished. These areas, created post-liberation, offer a place to contemplate the lives lost and the resilience of those who survived.

Turning to the camp’s darker corners, we reach the pistol execution areas. Here, SS guards shot prisoners at close range, often as punishment or reprisal. The walls remain pockmarked with bullet holes, and the blood ditch—a shallow trench—still scars the earth. Executions claimed around 4,000 lives, most of them Soviet prisoners of war, their deaths a grim fraction of Dachau’s toll. This site, though small, speaks to the brutality that defined the camp’s operation. Trees have grown since 1945, softening the scene, but the history cuts through. Imagine the silence before the shots, the terror of those final moments. It’s a place that demands stillness, a pause to honor those who died here.

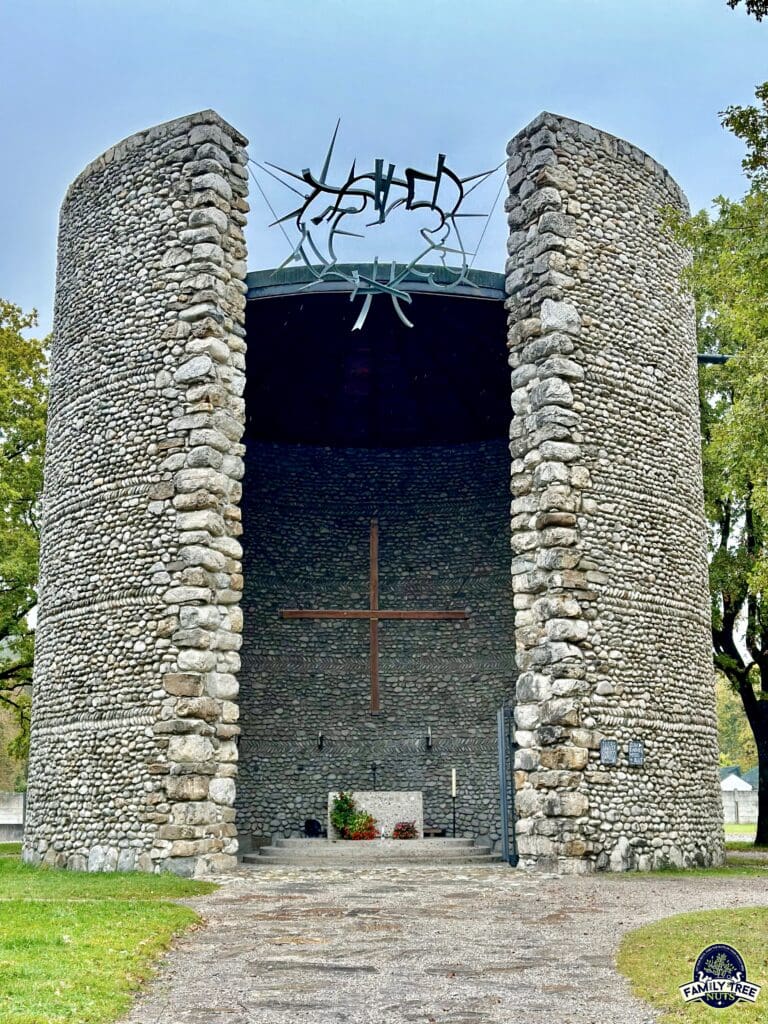

Dachau is known for its sadness and despair, but faith persisted here, reflected in the three chapels and monastery on the grounds. The Catholic Chapel of the Mortal Agony of Christ, built in 1960, curves gracefully with a circular design—a postwar addition for remembrance. The Protestant Church of Reconciliation, completed in 1967, angles sharply into the earth, symbolizing descent and redemption. The Jewish Memorial, a stone structure from 1967, slopes downward into the earth, symbolizing loss but crowned with a menorah for hope, honoring the many Jews held here, especially in the camp’s later years. Each faith found a voice here after the war, reclaiming humanity from the ashes.

Nearby, the Carmelite Monastery, established in 1964, houses nuns who pray for atonement. These sacred spaces, all post-liberation, mark a shift from suffering to reflection.”

Security defined Dachau’s perimeter. Seven guard towers, spaced along the walls, gave the SS clear sight lines. The walls, topped with electrified barbed wire, enclosed the camp, while ditches beyond them slowed escape attempts. From here, they controlled the morning roll calls, which was sometimes hours of standing in freezing cold or searing heat, counting the living and the dead. The tower’s shadow still falls across the gravel. It’s a reminder of the power that ruled this place. Outside, pill box guard positions—small concrete bunkers—fortified the exterior. Escape was rare; most who tried were shot or recaptured. This system ensured total control, a constant reminder of captivity.

Scattered across the site are memorial statues. The most striking is the Unknown Prisoner, a bronze figure in a tattered coat, head bowed but defiant, unveiled in 1950. Another, the International Monument, stretches as a skeletal frame of wire and stone, symbolizing the prisoners’ ordeal. These artworks, placed after liberation, honor the nameless and the known alike.

Finally, we enter the museum, housed in the former maintenance building. A large wall map charts Nazi concentration camps across Europe, showing Dachau as the first. Another map traces the origins of prisoners from over 30 countries, from Poland to France to the Soviet Union, even Ireland! A detailed model of the camp recreates its layout as it stood in 1945. Propaganda posters line the walls, alongside old photos military men, prisoners with gaunt faces and camp life. The beating table, a wooden slab used for corporal punishment, sits as a chilling artifact. Panels trace Dachau’s timeline: from its opening under Hitler’s regime to its liberation by American troops on 20 April 1945. The exhibits don’t shy away from the horror, but they also honor resilience. These exhibits document the camp’s operation and the lives it consumed.

Today, Dachau is a memorial site, open to the public since 1965. Over a million visitors come yearly, walking its grounds and museum to learn its lessons. Germany preserves it deliberately—not to hide history, but to keep it visible, ensuring the atrocities of the era are never forgotten. You can visit daily, free of charge, with guided tours available. Dachau isn’t just a site—it’s a lesson, a warning, a memory etched in stone and silence.

So now we know the story and have seen the sights of Dachau. What do you think? Do the facts presented in this video match up with what you expected? Were you moved by what you saw? How did it effect you? What lessons can we learn? We’d love to hear what you have to say in the comments below. We are proud to share this information with all of you and be sure to see the video from here at the link below. And remember, Family Tree Nuts, let out nuts find the nuts in your family tree.

-Colonel Russ Carson, Jr., Founder, Family Tree Nuts