CIVIL WAR BATTLE THAT LAUNCHED CAREERS

President Abraham Lincoln said, “I hope to have God on my side, but I must have Kentucky”. During the Civil War, Kentucky was an important border state that was heavily fought over by both north and south. The state supplied thousands of men for both sides and a few key battles determined its fate. Many have said that if the Union had lost Kentucky, then they would have eventually lost the war. It was that important to both sides cause and The Battle of Middle Creek was one of the major pivot points of the region. Men from here in Floyd County fought on both sides, fired volleys at each other, and engaged in hand-to-hand combat against one another. Can you imagine that?

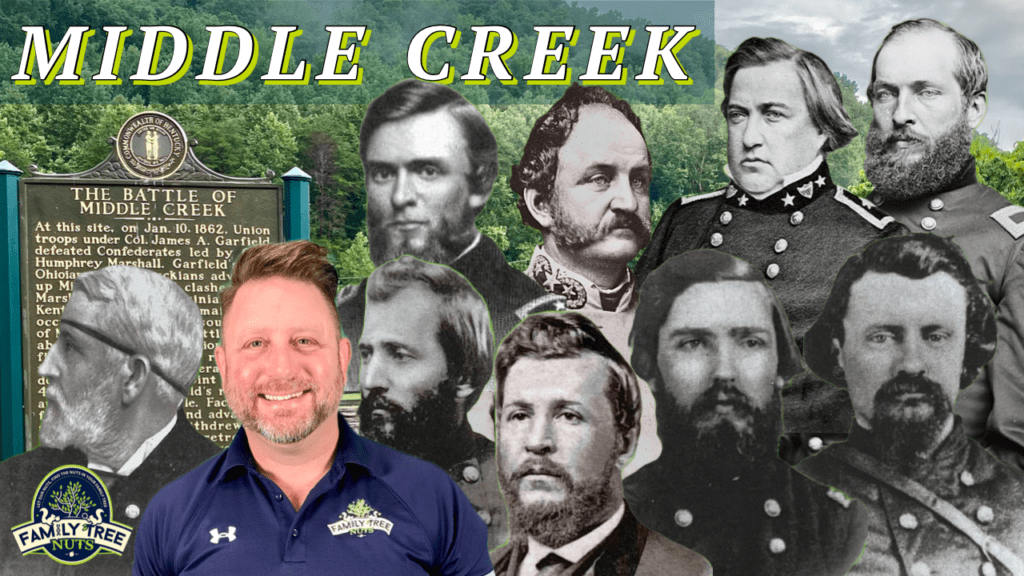

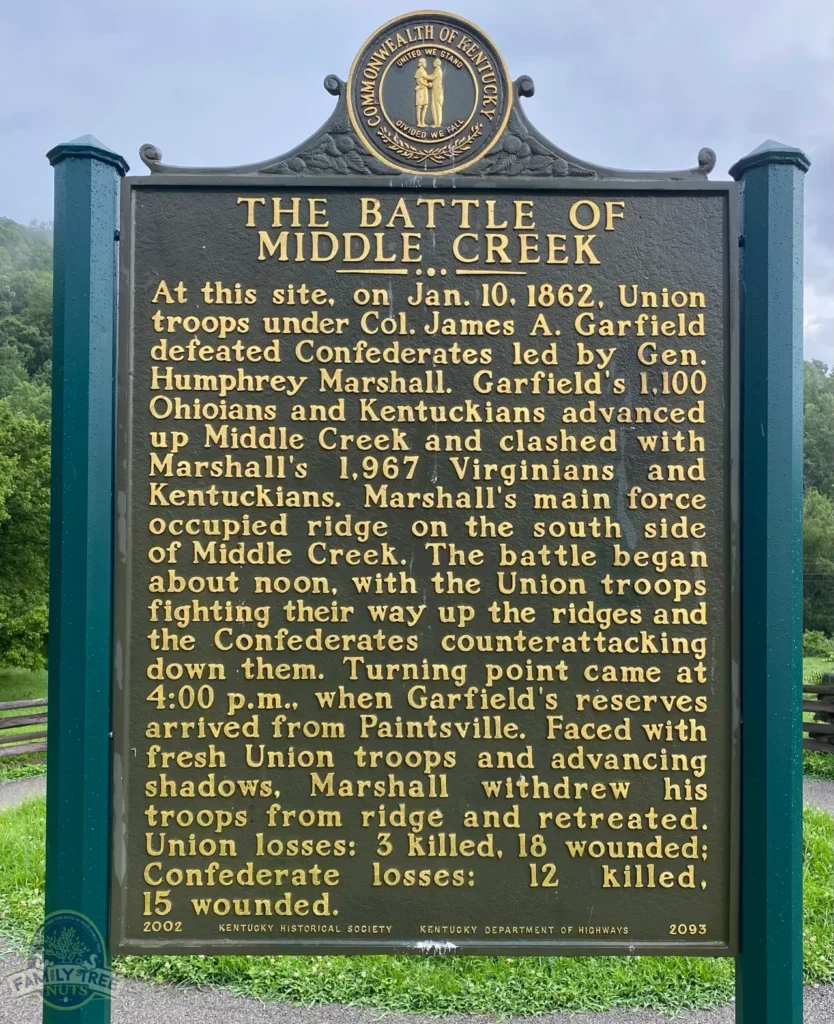

The Battle of Middle Creek happened early in the war, on January 10, 1862 and one of the most noted facts about the battle, is that it was the only battle that was personally commanded by future President James A. Garfield, who was then a Colonel. Garfield began to make a name for himself at this battle and went on to fight in the important battles of Shiloh and Chickamauga.

In order to understand the Battle of Middle Creek, we must first understand the back story of what lead to the battle. When the Civil War began, the Kentucky state politicians were torn as to which side to support in the war, but soon men around the state acted. The election of 1861 sent a Unionist majority to Frankfort and the new Legislature voted to suppress the rebellion. The people of Kentucky were then forced to decide which side they were on. Prominent secessionist men in Eastern Kentucky such as Jack May, Hiram Hawkins, Ezekiel Clay, James M. Thomas, Benjamin Desha, and others began to recruit men to form militia companies to fight for Southern Independence.

In September 1861, these men marched their units to link up in Prestonsburg, at the Samuel May Farm, which was a 400-acre farm complete with a steam-powered grist mill. The house was built in 1817 and is the oldest house in Prestonsburg and was built by Samuel May, the son of Revolutionary War veteran John May. Samuel was commissioned to build the counties first brick court house and served as a Kentucky State Senator, where he was instrumental in improving the Mount Sterling-Pound Gap Road, which is today U.S. 460. He later died in the California Gold Rush.

The new recruits camped all around the Samuel May house, and in late September, former United States Vice-President John C. Breckinridge fled arrest in Lexington, and passed through Prestonsburg on his way to Southwestern Virginia. He stopped by the Samuel May Farm and gave a moral boosting speech to the new recruits.

On October 2, their swelling numbers prompted the leaders to draft a letter to Jefferson Davis, which stated the following. His Excellency Jefferson Davis, President of the Confederate States of America. Sir, Our Legislature has betrayed us. We have marched with 1,000 men. Hundreds are gathering around our standard daily. We can have 5,000 men here in two weeks. We would most respectfully petition Your Excellency to send us immediately some experienced military man to command us, and place us upon a footing to make ourselves available in furthering the cause of civil freedom, in which we have enlisted, and to which we pledge our lives and our sacred honor”. The raising up of men into the thousands was encouraging for those who supported the southern cause but was alarming to those loyal to the Union. Colonel John Stuart Williams took command of the Confederate forces being formed. Williams was also known as “Cerro Gordo” Williams for his heroic actions in the Mexican-American War. The new Confederate troops began to disperse around the neighboring counties.

Upon hearing what the Confederates were accomplishing at t

he Samuel May Farm, the Union decided to act with a strong force. The Big Sandy Expedition began in mid-September 1861 when Union Brigadier General William “Bull” Nelson received orders to organize a new brigade in Maysville, Kentucky to conduct an expedition into the Big Sandy Valley region to cease the Confederate recruiting. Over the next few months, Nelson’s 5,500 troops split into two groups, one which pushed the Confederates out of Hazel Green, Kentucky, and the other out of West Liberty, Kentucky. The two-groups linked up in Salyersville, also known as Licking Station, and on October 31, 1861, stepped off for the final phase to push the Confederates out of Kentucky entirely.

On November 7, 1861, the Union troops met up with the remaining Confederates in between Prestonsburg and Piketon, now called Pikeville, and here the Battle of Ivy Mountain took place. Nelson had sent Colonel Joshua W. Sill to take the route along Johns Creek, to get behind the Confederates in Pikeville and prevent their escape. Nelson lead the remaining 3,600 men down the Old State Road, which today is Route 460, towards Pikeville. Heavy rains caused the road to be extremely muddy and that forced the Union troops to march in a single file line. The advanced guard was hit first, four men were killed, and thirteen were injured. The ill-equipped Confederates were firing old shotguns and muskets and Nelson jumped on a large rock and shouted “that if the Rebels could not hit him, they could not hit any of them”.

The 21st Ohio Infantry flanked the Confederates on a top of a hill and began to roll huge boulders down on the rebels causing them to scatter in all directions. As the Confederates retreated they burned bridges and chopped down trees to impede the Union’s pursuit. Colonel Williams made it to Pikeville and placed a rear guard to protect the retreat of the rebels to Pound Gap, Virginia. General Nelson made it to Pikeville and halted because he believed he had accomplished his mission to push the Confederates out of Kentucky and due to the lateness of the season and the Confederates lack of supplies, a counter attack was unlikely. Two weeks later Nelson received orders to bring his troops back to Louisville. Colonel Williams was surprised and fully expected the Union troops to pursue him into Virginia but after their evacuation of the area, he downplayed the Union victory saying that “Nelson had dispersed an unorganized and half-armed, barefooted squad that lacked everything, but the will to fight”.

The Confederates were determined to hold onto their support in Eastern Kentucky and in mid-December General Humphrey Marshall marched out of Wytheville, Virginia, through Pound Gap, and occupied Pikeville, Prestonsburg, and Paintsville. Union Major General Don Carlos Buell got word of the Confederate activity and sent Colonel James A. Garfield to take command of the 18th Brigade of the Army of Ohio to permanently drive the Confederates out of the Big Sandy Valley.

General Marshall was pushed back from Paintsville to Prestonsburg, where he thought he could ambush Colonel Cranor’s men coming from Salyersville, but Cranor went to Paintsville, and fell in behind Garfield, to reinforced the battle later. Marshall set up his men on the ridges and hidden positions looking over the valley of Middle Creek.

Garfield expected an ambush and sent scouts slowly into the valley to identify where the Confederates troops were. He sent his own personal guard of ten cavalry men to draw fire and when they did, he determined that the enemy had the high ground. He set up his command center at graveyard point. Garfield also wrote his wife a letter after the battle which included a map that he had sketched which has been valuable for us to understand the battle today.

Once Garfield knew the approximate positions of the enemy, he ordered his men to split into three groups and attack the ridge lines where the Confederates were set up to ambush the valley. Major Don A. Pardee’s men were pinned down by rebel sharpshooters. About this same time, Colonel Cranor arrived to link back up with the main force and Garfield ordered him to reinforce Pardee. Garfield then ordered Lieutenant Colonel George W. Monroe to select 120 Kentuckians to charge up the hill and assault the rebel sharpshooters. This detachment was quickly pinned down by the sharpshooters when Monroe ordered the men to fix bayonets and with loud yells they charged up the steep ridge to fierce combat of Kentuckian versus Kentuckian. Monroe’s men caused the rebels to fall back which opened the line for Pardee and Cranor to continue to advance. It is said Monroe’s charge likely determined the battles outcome.

The Confederates had artillery and the Union did not. This was thought to be an advantage for the rebels but ended up almost worthless. The muddy conditions caused the guns and their support wagons to be very difficult to move. The artillery unit was formerly a militia unit from Nottoway County, Virginia and their ammunition had likely been in storage for more than twenty years which caused it to be faulty. Marshall was forced to retreat and fall all the way back into Virginia and give the Union the victory in the battle. The Confederates never again had as much of a hold on Kentucky as they did before this battle.

Despite over 3,000 men engaging in combat at the Battle of Middle Creek, the casualties were very small. Different numbers can be found different places. The Confederates had at least twelve killed, and as many as 57 wounded. The Union had three men killed and reports from 18-24 wounded. One of the Union units that participated in the battle was the 14th Kentucky Infantry which had 1 killed, and 2 wounded. One of the two wounded was Private Thomas Jefferson Bellomy, who after the battle was sent by train to a hospital in Lexington. Three days later he passed away and is buried in the Lexington Cemetery. He was my 4th great-uncle which makes this story very real to me. My 5th Great-Grandfather Bennett Bellomy was awarded a pension for his son’s service and ultimate sacrifice. Thomas had mustered into service on December 10, 1861, just a month before he was wounded at this battle and eventually passed away. Just a month. Another interesting note is that my 3rd Great-Grandfather Bernard Bellomy who was two-years-old at the time of the 1860 Census, lived in the same household as Thomas. Having photographs of people who knew someone that lived a story in history makes it incredibly more real.

Now let’s take a look at some of the other men of note that took part in the Battle of Middle Creek and their experiences after it. Many of these men went on to do amazing things and it is interesting that they all have fighting in the Battle of Middle Creek in common.

The first is the Union commander Colonel James Garfield who was born to modest beginnings in a log cabin near Cleveland, Ohio. He wanted to be a teacher and graduated from Williams College before becoming a Latin and Greek professor at Hiram College. He was an ardent abolitionist and in 1859 he became an Ohio State Senator. When the war broke out, Ohio Governor Dennison appointed Garfield a Colonel and asked him to raise up a regiment. After his victory at Middle Creek, Garfield was promoted to brigadier general and had much more success in the war. He used his popularity to rise in political ranks eventually being elected the 20th President of the United States in 1880. A little more than six months into his office he was assassinated. He was only 49-years-old.

Garfield’s Confederate counterpart in the battle was Brigadier General Humphry Marshall. Marshall came from a distinguished Kentucky family and was the son of a prominent Frankfort lawyer and the nephew of Chief Justice John Marshall. He graduated from West Point in 1832 and served with the U.S. Mounted Rangers during the Black Hawk War. He later became a lawyer in Louisville before once again taking up arms serving as a Colonel in the Mexican-American War. He won distinction by leading a gallant cavalry charge at the Battle of Buena Vista. Later he served as a United State Congressman and was President Millard Filmore’s commissioner to China. When the Civil War began, Marshall raised up a large number of troops for the Confederate Army and was made a Brigadier General. After the battle of Middle Creek, many wondered if he was a capable leader and he was never again given what he felt as a suitable command. In November 1863 he was elected to the Confederate Congress and worked as a lawyer in Louisville after the war.

As we discussed earlier, Colonel John S. “Cerro Gordo” Williams was a hero of the Mexican-American War and important to organizing recruits in Eastern Kentucky, and took part in the battles in the fall of 1861. After the Battle of Middle Creek, Williams was promoted to brigadier general and placed in command of the Department of Southwestern Virginia. In 1863 he commanded the cavalry brigade which contested the advance of Burnside’s Corps into Eastern Tennessee. He also played a key role in the Confederate victory at the First Battle of Saltville.

Confederate Captain Ezekiel F. Clay was the son of United States Congressman Brutus J. Clay, a prominent Bourbon County Stock Breeder and president of the Kentucky Agricultural Association. He was also the nephew of the fierce abolitionist Cassius Marcellus Clay, who was Lincoln’s Minister to Russia. How interesting it is that Captain Clay fought for the Confederacy while being the nephew of one of the most well-known abolitionists around. Clay organized a company of volunteers in Bourbon County and brought them to the Samuel May Farm as we discussed above. He and his men participated in the Battle of Ivy Mountain. After the Battle of Middle Creek, he served with General Marshall’s Army of Southwestern Virginia until the spring of 1863 when he and his men were transferred to Georgia to serve under General Nathaniel Bedford Forrest. He and his men rode with Wheeler’s Cavalry on their raid through middle Tennessee. At Shelbyville, Clay was wounded but was healed in time to take part in the Knoxville Campaign. In April of 1864 he led a brigade of cavalry on a raid into Eastern Kentucky, and at Puncheon Creek, he was defeated and badly wounded in the eye. He was sent to a POW camp on Johnson’s Island, near Sandusky, Ohio, and stayed there until the end of the war. After the war he returned to the family farm in Bourbon County, Kentucky, known as Runnymede and built it into one of the finest Kentucky thoroughbred farms in the world.

Lieutenant Colonel George W. Monroe was born in Adair County, Kentucky but grew up in Frankfort where his father was a prominent judge. Monroe first saw combat at the Battle of Middle Creek and as we mentioned above, he was the one who lead the Union charge up the steep hills against the rebel sharp shooters, and that action likely won the battle for the north. Monroe and his men saw plenty of combat after the battle of Middle Creek including serving under General Sherman’s command during the expedition to Chickasaw Bayou, Mississippi in December, 1862 where he was wounded. Soon he was promoted to Colonel and later led an unsuccessful charge at Chickasaw Bluffs, on the Yazoo River above Vicksburg. On March 18, 1865 Abraham Lincoln himself promoted Monroe to Brigadier General for his “gallant and meritorious services during the war and for the Union cause”.

Major Don A. Pardee was born in Wadsworth, Ohio and trained at the United States Naval Academy. He played a key role in the Battle of Middle Creek by leading the main assault. After the battle he fought in the Battle of Pound Gap in which his leadership earned him a promotion to Lieutenant Colonel. He later fought in the battles of Rogers Gap, Chickasaw Bayou, and Port Gibson. He was eventually promoted to Brevet Brigadier General and practiced law in New Orleans after the war. Later his former commander, James Garfield while president, appointed Pardee to the United States Circuit Courts for the Fifth Circuit and he served on the U.S. courts until his death in 1919.

Lieutenant Colonel Lionel A. Sheldon was born in Worcester, New York but at a young age moved with his parents to Lagrange, Ohio. He graduated from Oberlin College, and later law school in New York. Before the war he served as a brigadier General in the Ohio militia, and then later, at the beginning of the war, was made a Union army lieutenant colonel after raising six companies of men in only six days. Shortly after the Battle of Middle Creek, Sheldon was promoted to colonel and second in command to Garfield. His unit saw action under Sherman at Chickasaw Bayou and Cumberland Gap. Later he and his unit fought under Major General Ulysses S. Grant at Port Gibson and Thompson’s Hill where he was wounded in the hand by a musket ball. He was healed enough to the fight at Vicksburg. After Vicksburg he spent the rest of the war building forts and repairing levees. He was eventually promoted to brevet brigadier general and after the war practiced law in New Orleans. Sheldon remained friends with James Garfield, and shortly after Garfield took office, Sheldon took the office of Territorial Governor of New Mexico. In 1888, he moved to Los Angeles, California and practiced law, and eventually moved to Pasadena, California until his death in 1917.

Lieutenant George W. Gallup was born in Auburn, New York but moved to Ohio and eventually Louisa, Kentucky where he practiced law. When the 14th Kentucky Infantry was formed, he originally enlisted as a Private but after helping with the recruitment of men for the unit, was promoted to quartermaster and the rank of 1st lieutenant. A few months after the Battle of Middle Creek, Gallup was promoted to lieutenant colonel, and later to Colonel, and made the commander of the 14th Kentucky. That’s right, he was then the commander of the unit that he had joined as a Private. From August 1863 to May 1864 he served as the Commander of the Military District of Eastern Kentucky. He was ordered to serve under General Sherman in the Atlanta Campaign. After fighting in Atlanta, he reported back to his position of Military Commander of the Military District of Eastern Kentucky and was promoted to brevet brigadier general. He was one of the few men that went from private to a general during the war.

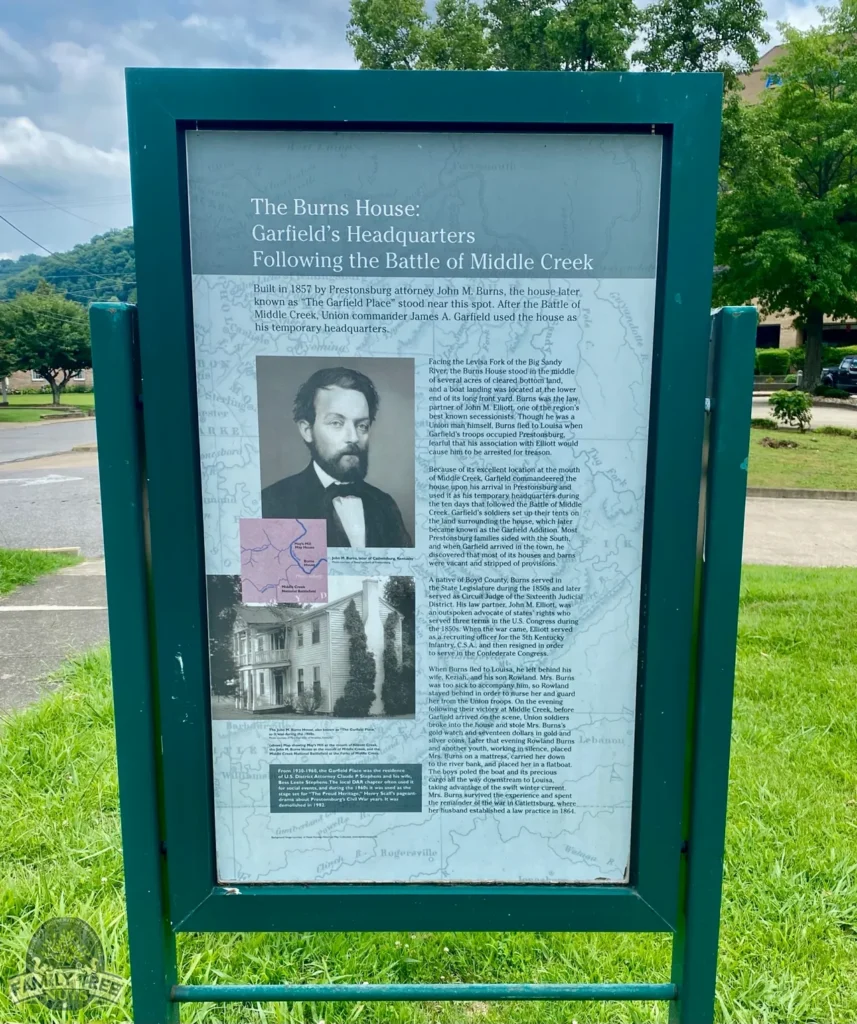

After the Battle of Middle Creek, the Union army occupied Prestonsburg and Garfield set up his command in the Burns House, which was built in 1857 by Prestonsburg attorney John M. Burns. The house had a strategic position facing the Levisa Fork of the Big Sandy River. Burns had served in the State Legislature, and as a circuit judge. Burns supported the Union, which was interesting because he was a law partner with John M. Elliot, who was one of the area’s most know secessionists and had served in the United States Congress in the 1850s. Elliot served in the Confederate Army as a recruiting officer in the area before serving in the Confederate Congress. Even though Burns was a supporter of the Union, after the Battle of Middle Creek he felt that he should flea to Louisa because he feared that his association with Elliot would cause him to be arrested.

Burns left behind his wife Keziah, who was too sick to travel, and his son Rowland to take care of her. On the night of the Union victory at the Battle of Middle Creek, and before Garfield arrived on the scene, Union soldiers broke into the house and stole Mrs. Burns’ gold watch and seventeen dollars in gold and silver coins. Most of the people of Prestonsburg supported the South and the Union troops found almost all of the houses and barns had been stripped of provisions. Later that night Rowland and his friend carried Keziah on a mattress down to the river where they loaded her on a flat boat and poled her to Louisa. Keziah survived and stayed the remainder of the war in Catlettsburg, where her husband practiced law.

Soon after the family fled Prestonsburg, Colonel Garfield arrived and made the home his temporary headquarters for the next ten days. The Union troops set up tents all around the house which later became known as “Garfield’s Addition”. From the time of Garfield’s occupation of the house until its destruction, the house became known as Garfield Place.

The house changed hands several times until in 1895, Maggie Leete purchased the house for $450. Mrs. Leete restored the house and turned it into a Prestonsburg showplace. The Leete’s held Colonial Teas, complete with powdered wigs and colonial dress. The house became Floyd Counties first museum. In 1932, Congressman James R. Garfield, the son of President Garfield came and toured the house. He was shown an old cap and ball pistol that a carpenter had found behind a plastered wall. The Congressman said that it was likely his fathers because he was very fond of that type of weapon.

In the 1960s the house was the stage for the drama entitled, “The Proud Heritage” which was about Prestonsburg during the Civil War. The house passed hands several more times within the family and was occupied until 1977. Sadly, the house was demolished in 1982.

In 1916, 54 years after the Battle of Middle Creek, Floyd County Civil War veterans gathered on the steps of The Bank Josephine for a reunion and to have their picture taken. Can you imagine the stories that these men shared? I wonder if any of them still held animosities toward each other?

Today at the battlefield is a park that is led by The Middle Creek National Battlefield Foundation, Inc. and they have many plans for the future of the park, including a visitor’s center, library, and a multi-media theater. Here at the park there are several historic signs explaining much of the history of the battle. A statue of Abraham Lincoln seated in a chair, similar to the one in the Lincoln Monument, is on one side of the parking lot, at a picturesque location between the gap in the ridgelines. There are two walking trails, one Confederate and one Union. Along each route you will find interpretive signs explaining many things about the battle and the history leading up to it. The park is free, open day light hours, and well worth the visit.

The Battle of Middle Creek is one of those lesser known battles of the Civil War that doesn’t get the attention that it probably should. The battle happened very early in the war, and I often wonder if the local folks thought that it would be one of the major battles fought. At the time of the battle in January 1862, no one could imagine the awful three and a half years that were to come. After the battle here, the fighting in Kentucky was far from over, with dozens of battles, skirmishes, and raids still to come. However, this battle remains important because the Confederacy never again had as much of a foothold in Kentucky as they did before this battle and that makes it a pivotal and important event.

– Colonel Russ Carson, Jr, Founder, Family Tree Nuts