SHARPSHOOTER DESERTER FINGERS SHOT OFF! CIVIL WAR HISTORY

He could shoot so well that he was assigned to an elite unit. He deserted, more than once, was arrested, court martialed, and spent time in a military prison in Richmond. He had fingers shot off of both hands, was captured by General George Armstrong Custer, and served time as a POW. This is the story of Pvt. William Tucker.

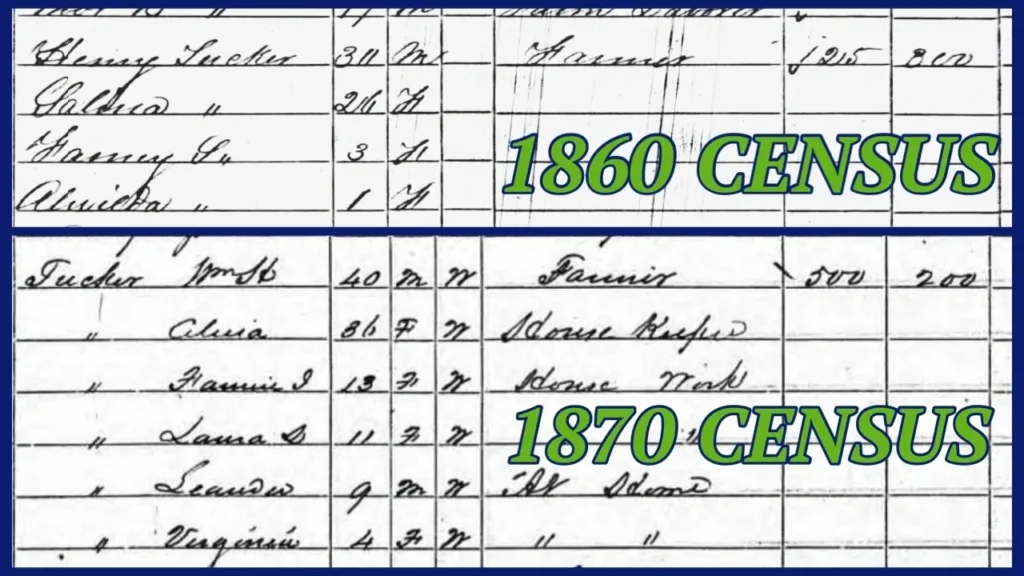

I was working on a family tree for a client and came across the amazing story of his 4th-great-grandfather. The more that I discovered about him, the more that I knew that I wanted to share his story with all of you. William Henry Tucker was born on Valentine’s Day, 14 February 1827, in Botetourt County, Virginia. He married Salina Crawford in 1856, and by 1860, he lived in the Valley of Barber’s Creek, Craig County, Virginia, with two baby girls. Before the Civil War, he had had a decent start to life. His real estate was valued at $1,215 and his personal estate $800, which is definitely above average for the time. As you will soon see, the upcoming war had a tremendous impact on him in many ways.

William heard Virginia’s call and enlisted in Independence, Grayson County, Virginia on 2 September 1862. He was originally assigned to the 51st Virginia, but his commanders soon learned that he was a great shot and soon he was transferred to the elite 30th Battalion Sharpshooters. Military life must have not been what he was expecting because just four days after enlisting he was listed as absent without leave. I remember my first few days in the Marine Corps so I can definitely relate to what Private Tucker was thinking. He must not have stayed gone long because soon he was in the hospital, and from there on 5 October 1862, he took off a second time and was listed as a deserter.

William either returned on his own, or was caught and arrested, because on 9 June 1863, eight months after being listed as a deserter, he was court martialed. He was sentenced to serve time in the military penitentiary in Richmond. Just a few months later, on 31 August he was released from prison by order of the Medical Executive Board, possibly because of conditions of the prison, or the army needing as many men as they could get.

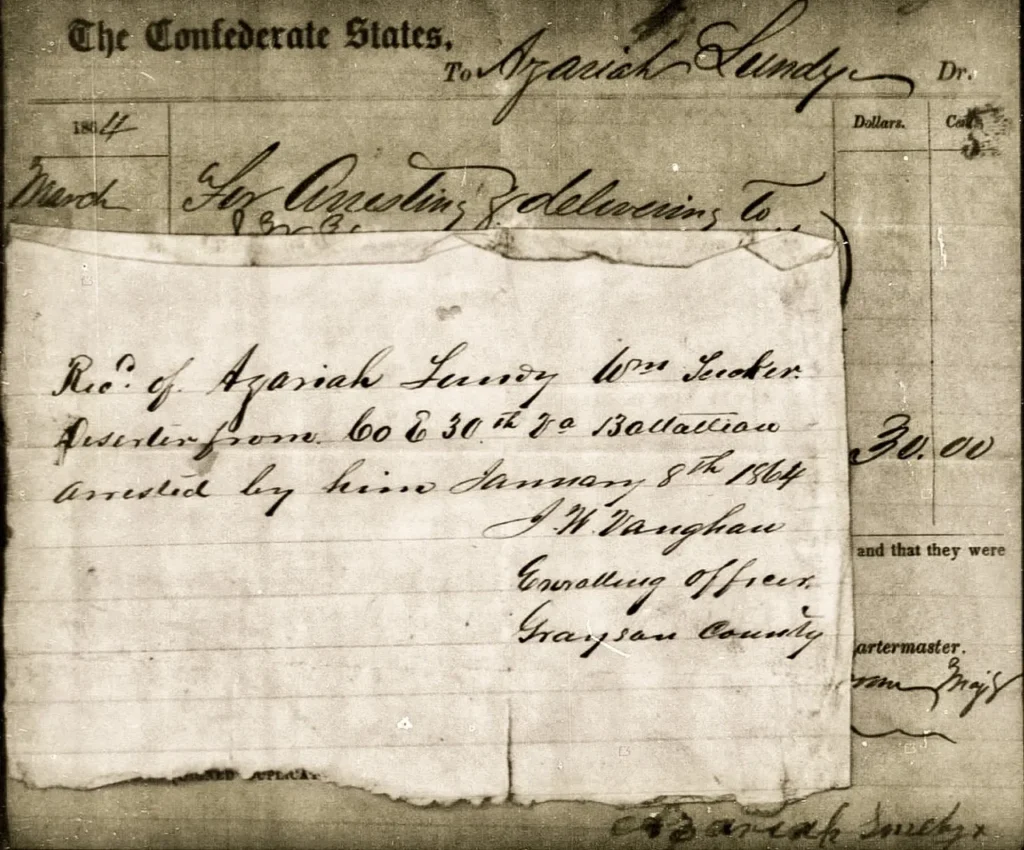

Now, after taking off twice and even serving some time in a military prison, you’d think young William was in it for the long haul of the war, right? Well, apparently not, because at some point between 1 September and the end of the year, William deserted yet again. In December, he claimed that his horse was stolen by Yankees during General Averill’s raid. He later in 1871 applied to be reimbursed $200 for the loss of his horse. A few weeks after his horse was taken, he was arrested on 8 January 1864 and returned to his unit by a Mr. Azariah Lundy who was paid $30 for his service. It is not known if William was punished for deserting again.

William was back in the hospital on 25 April 1864 for conjunctivitis, which is pink eye. He was at General Hospital #13, in Richmond, Virginia. Then on 2 or 3 June 1864, while fighting in the Battle of Cold Harbor he was severely wounded. In William’s words on his 1890 application for a soldier’s disability pension, he said he was “in a fight in the lines of General Lee’s Army near Gaines Mill”, he suffered “a gunshot wound in the left hand destroying two fingers and two on the right hand”. He mentions later on his statement that “part of both hands and fingers have been lost”. His pension application is signed by his own hand. No records have been found of him missing time in the hospital again but it can certainly be assumed that he did.

The final stage of the war for William was on 2 March 1865, just weeks before the war unofficially ended at Appomattox. William and his unit were under the command of General Jubal Early, and fought against Union Generals Philip Sheridan and George Armstrong Custer at the Battle of Waynesboro. William’s entire unit was captured or destroyed as Custer pursued them in retreat. William was made a prisoner of war. The officers were sent to Fort Delaware, Delaware and the enlisted men went sent from Harper’s Ferry, West Virginia, to Point Lookout, Maryland.

At Point Lookout Prisoner of War Camp, he was recorded to be 5’6” tall, with a fair complexion, dark hair, and grey eyes. Records like this give us an awesome snap shot of what our ancestors looked like. He took the Oath of Allegiance on 21 June 1865 and was finally released from military service and returned home. William applied for a soldier’s disability pension and was awarded $15 a month.

Another interesting note about William and the Civil War is that through his mother, he was a 2nd cousin, twice removed of Brigadier General Elisha F. Paxton who died while leading the Stonewall Brigade at the Battle of Chancellorsville. I wonder if he knew that he was a cousin of this famous general?

The war had more than a physical effect on William Tucker. If you remember what I said earlier that before the war in 1860, his real estate was valued at $1,215, and his personal estate valued at $800. After the war, in 1870, his real estate was then valued at only $500, and his personal estate only $200, much less than half of what it was worth before the war. We learned that the war had lasting effects on William, physically, financially, and mentally, and likely impacted his family for generations to come.

William was granted a soldier’s disability pension in 1890, for $15 a year and lived the rest of his days as a farmer in Craig County, Virginia, until he died of Bright’s Disease in 1906. He is buried in Andrew Chapel United Methodist Church Cemetery, in Buchanan, Botetourt County, Virginia. His wife filed for a widow’s pension in 1915, and was granted a pension of $30 a year.

I also want to mention that it was extremely common for soldiers to desert during the Civil War, and they did so for many reasons. Often their enlistments were involuntarily extended, they got news from home that required their attention, or sometimes the horrible conditions and helplessness that they felt with the war, caused them to just simply have enough. The fact that Private William Tucker deserted more than once does not reflect negatively on his character, valor, or his manhood. It simply shows a very clear example of how desperate the times were for so many.

Wow, now we know the story of Private William Tucker. What are your thoughts? Were you moved by his story? How would it affect you if you discovered a story like this about one of your ancestors? I’d love to hear what you have to say in the comments below.

When we discover stories about our ancestors, especially like this one, history becomes tremendously more real. The battles that we read about or drive by, begin to have a different impact on us and we are bestowed with a deeper enlightened understanding. Discovering and preserving stories like this is a passion of ours and we are so proud to be able honor Private William Tucker by discovering him and sharing his story with his descendants, and all of you. Be sure to see the video at the link below.

-Col. Russ Carson, Jr., Founder, Family Tree Nuts