BEGINNING OF THE END FOR BRITISH! KINGS MOUNTAIN!

It was the beginning of the end for the British Army in the American Colonies. Recently we visited Kings Mountain National Battlefield, in South Carolina. This battle was the beginning of the end for the British. As we all know, American Patriots first fired on British soldiers in 1775 at Lexington Green, in Massachusetts, and that event set in motion a war that would not conclude until the surrender of the British army at Yorktown, Virginia, in September of 1781.

Early on, all of the action was located in the northern colonies, and the British strategy was to split New York in two, therefore cutting off New England from the rest of the colonies thereby forcing them into subjugation and bringing the war to an early end. After several battles including the unexpected Patriot victory at Monmouth Courthouse, and also at Saratoga, the British realized that the young Continental Army was going to be a force to be reckoned with. At that point, the war ground to a halt in the region, so the British Army changed it strategy and moved the war to the southern colonies.

They believed that the largely rural and agricultural population would support the Crown, especially in light of their significant exports back to England and the West Indies. The plan was for Sir Henry Clinton to take Charlestown, present day Charleston, by force so that a base of operations and supply could be established for the army. Initially, it was a great success for the British as they took the city and along with-it hundreds of Continental soldiers. In the meantime, George Washington sent reinforcements down to the Continental Army in the south, but it was too late. Charleston was lost and hopes to contain the powerful British Army in the south were not good.

Once established, the British plans were to move north through South Carolina, and into North Carolina hopefully gaining support amongst the population all along the way. Little did they know that an aggressive civil war was already taking place amongst the rural populations across the mountainous South Carolina upstate. Family against family, brother against brother, as the notion of independence was hotly being contested amongst the farmers and settlers.

After the fall of Charleston, Sir Henry Clinton retired to New York and left his second in command, General Charles the Earl Cornwallis to complete the defeat of the southern colonies, by gaining support from the population, and moving back toward the northern colonies to bring the war to an end. In the early days of warfare, large armies moved slowly with miles of equipment, people, and followers. To advance on an enemy took time, so it was common to have fast moving light infantry that would scout ahead of the army to secure supplies and warn of possible danger.

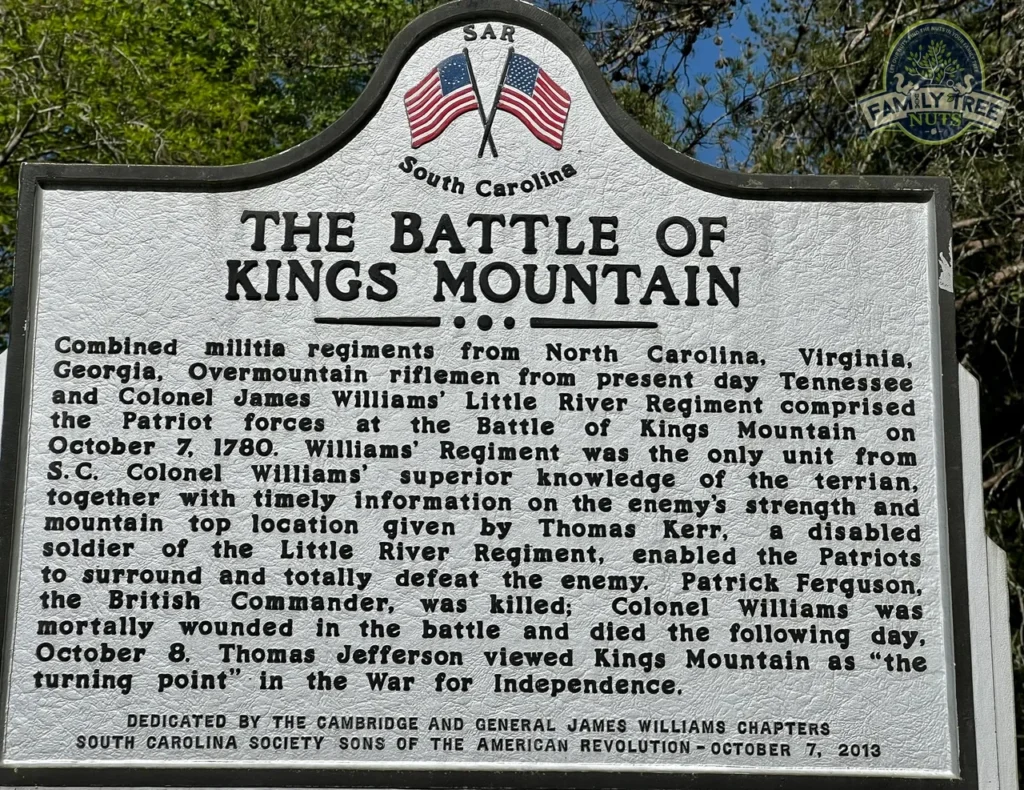

The British Army in South Carolina had two such advance groups, one commanded by Colonel Banastre Tarleton, known for his brutal tactics and murder of prisoners, and the other commanded by Colonel Patrick Ferguson. After Charleston, the first major battles at Camden, Monks Corner, and The Waxhaws were victories for the British, then they started their move north toward North Carolina. Patrick Ferguson and his light infantry was to move to the west of the main army to protect the left flank, from the patriot militias located in the mountains of the South Carolina backcountry. He sent warning to the settlers on the western side of the Appalachians that they were to swear allegiance to the Crown, or he would “march over the mountains, hang their leaders, and lay the country to waste with fire and sword”.

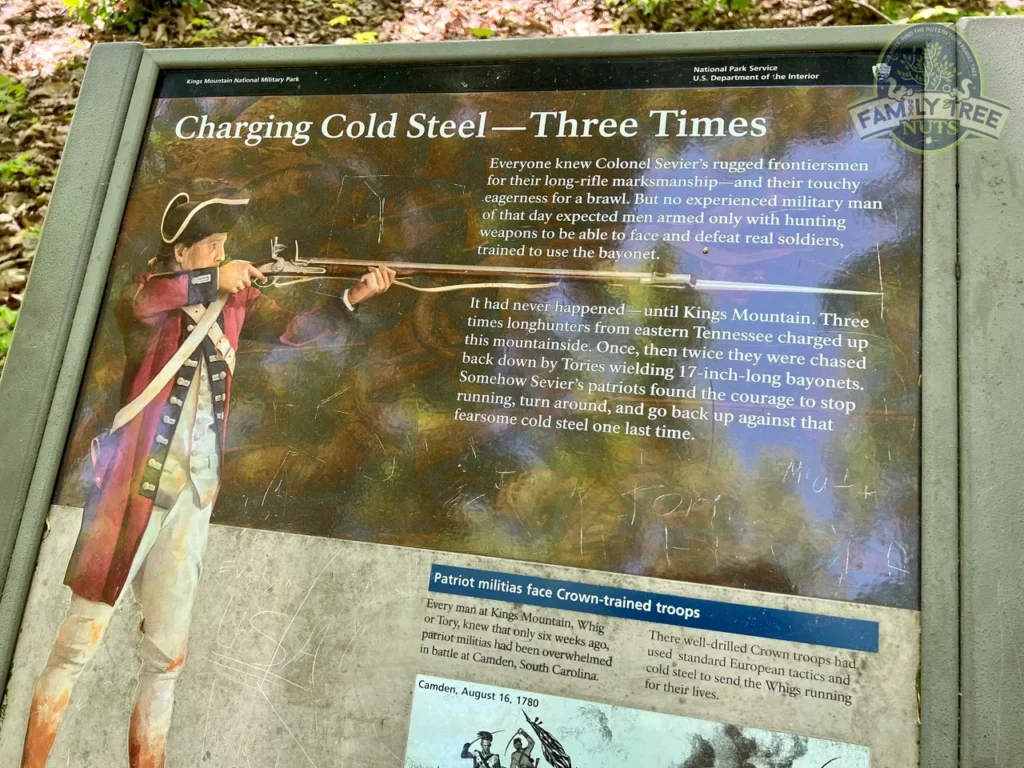

The settlers, soon to be known as the Overmountain Men led by Colonel Charles McDowell, wasted no time as they gathered at the Sycamore Shoals, in present day Elizabethton, Tennessee, and crossed the mountains to look for Ferguson and his men. Pioneers such as John Sevier, William Campbell, and John Crockett, the father of Davy Crockett, were some of the Overmountain Men that joined the fight. In the meantime, British Colonel Ferguson moved north and west closer to the mountains and chose what he thought was the best place for battle by positioning his men on top of a hill called Kings Mountain. A place that was easily defensible from all sides due to its steep slopes. His assumption was that reinforcements from Lord Cornwallis’ army would soon follow along with loyalist militias from the region, therefore giving him an even stronger defense.

On October 7, 1780, the Overmountain Men, along with other patriot militias, arrived in the vicinity of Kings Mountain and planned to surround it and attack from all sides by pushing up the slopes until the defenders were either killed or captured. That’s exactly what they did. Within a few hours the battle was over, Ferguson had been killed, and over 650 of his original 900 soldiers were killed or captured.

It was a significant victory for the patriot cause because the British Army in South Carolina had lost their light infantry protection on the left flank, and they were now vulnerable to attack. Knowing that, General Cornwallis and his last remaining light infantry commanded by Colonel Tarleton would be on the hunt Patriot Colonel McDowell and his Overmountain Men. McDowell made a quick exit out of the region the same day of the battle, and along with their slow-moving prisoners made their way back across rivers and into the relative safety of North Carolina. The goal was to get the prisoners secured in Richmond, Virginia before the British could catch up and liberate them.

So, the race was on. Colonel Tarleton was in fast pursuit to catch up and engage with his light infantry. At this point, the patriots gained a tactical advantage by seeming to retreat quickly, but only for the purpose of luring Tarleton’s legion further away from the main British Army. A few months later they met at The Cowpens and the 2nd battle against Cornwallis’ last fast moving light infantry took place in January of 1781. The Patriots easily defeated Tarleton’s light infantry. The result? General Cornwallis’ main army was now totally unprotected on all sides, and both of his advanced legions had now been destroyed.

At this point, General Cornwallis made a serious tactical error. With both of his light infantries gone, he attempted to turn his main army into the same light infantry by unloading all of their weight and supplies and he set out to chase Colonel McDowell and the Overmountain Men down to destroy them. As the race went further, and further away from the North and South Carolina coast, it became evident to the British army that they would not catch up with the patriots. The Battles of Kings Mountain and Cowpens set into motion a chain of events that would eventually lead to the surrender of General Cornwallis and the British Army that same year in October, in effect ending the American Revolution.

At the Battle of Kings Mountain, the British lost and that was strike one. A few months later they lost again at The Cowpens, and that was strike two. Finally, it was strike three at the Battle of Yorktown. They were out! Be sure to see our video from Kings Mountian below.

Scott Denney, Historian, Family Tree Nuts